That's just, like, your opinion, man…

My darlings are too darling to be killed.

How good are you at asking for feedback? How well do you tend to take it?

The answer to those two questions could have a massive impact on your success in work and life.

Various studies have shown that organizations that have a culture of giving feedback have higher engagement and lower turnover, while one study found that asking for feedback improved individual performance by 4.6 times.

But it’s not just at work. Feedback can be an important way to grow in relationships, sport, happiness, and comedy.

I shared last week that I was excited, but also anxious, about my upcoming Dry Bar Comedy Special.

So I did what every other introverted neurotic person does when anxiety starts to creep up: I (over?) prepared.

Between now and February 10th (the date of the taping), I booked 10 (and counting) shows and virtual events where I can run through material from the special and get feedback from the audience (either in the form of laughter or by asking questions).

The first such run-through happened yesterday as part of the Humor That Works January Happy Hour, and I have to say, the feedback was fantastic. This is one heck of a smart community we have here (if I can say so myself.)

If you were on that call, thank you.

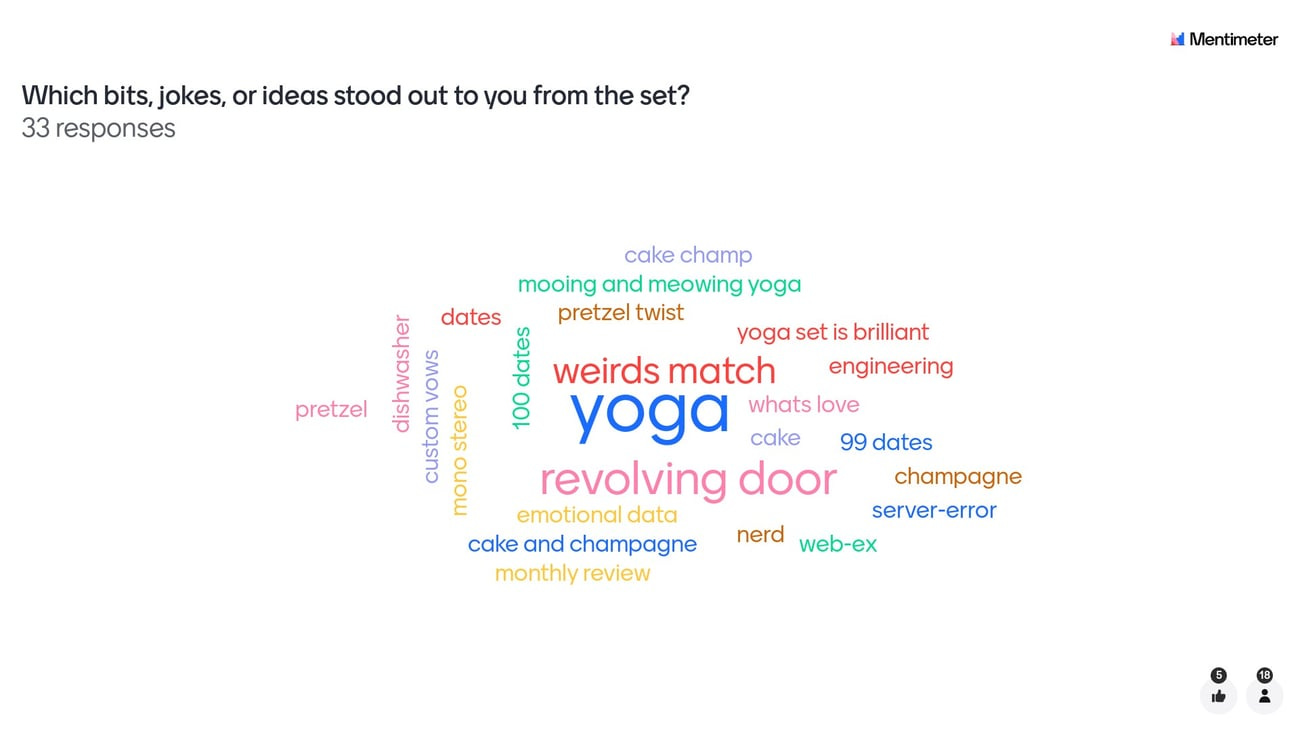

Over the course of an hour, I performed the potential content I’ll be using in the special, got feedback on the set, calculated ratings for specific jokes, heard tips on what to improve, and even took a few suggestions on what I might wear during the taping - for whatever reason, nobody liked my idea of wearing a onesie :(

People shared some overall excitement:

I am SO excited for you having this opportunity! Brilliant material.

Good stuff...well done, Drew!

Thanks for letting us join this! Can't wait to see the final set!

And which bits they really liked:

Loved the listing of all the nerds

You had me at spreadsheet!!

Haha conundrum of revolving door etiquette

But also gave specific notes:

Haha dating interview - I want more of that

Shorten the joke to: if I did helium, only dogs would hear me

The montage is very clever but feels kind of fast and goes on too long.

One the one hand, everything I’m taking away from the session is going to make the Dry Bar Special stronger.

On the other… I’d be lying if I said taking feedback from people is easy.

Because, at the end of the day, the content is mine. I lived it, wrote it, performed it, and tweaked it, over and over and over and over again. And here you are, some person just surfing into my Zoom room trying to tell me how to do comedy…how dare?

Just kidding… mostly.

I specifically asked for this feedback.

And it turns out that “asking for it” (feedback, not a knuckle sandwich) might be critical to giving and receiving feedback better.

One study found that, when people were given spontaneous feedback (i.e. they didn’t ask for it), their heart rates jumped enough to show moderate or extreme duress. The crazy part is so did the heart rate of people who had to give the spontaneous feedback. Not only did it make both people more anxious, the feedback was also more generic and less productive.

So it was a worse experience with a worse outcome. Lose lose.

But when you ask for feedback, you’re giving people permission to provide an honest, constructive perspective that you can actually do something with.

The fact that I had asked for feedback on my material (and even set up a Mentimeter poll with questions like “What didn’t you like about the set?”) made it easier to stomach some of the more critical notes. And to be clear, much of it was very positive and along the lines of “this was great, keep doing it!”

But “this is great” doesn’t help you improve as much as “this was too wordy” or “I didn’t understand this” or “more cowbell… I mean object work.”

And yet that didn’t stop me from having to google research as to why feedback can be so hard to hear and accept.

After the run through today, I had a conversation with an old friend from my improv days and I was sharing how I was incredibly grateful for the feedback shared but also slightly defensive of some of the suggestions that were given.

I mean I know there’s an entire cliche in writing that you have to “kill your darlings,” that the things you love just may not be in the best interest of the piece. But in my head I thought, “that might be true of your so called ‘darlings’ but my darlings are too darling to be killed.”

He (very wisely) reminded me of a maxim from improvisation: when it comes to coaching improv, there is no “should.” As in, a good improv coach never says, “You should have done [blank].”

Because improv scenes are all made up. Yes, you COULD have chosen to marry the swamp creature you just met, or you could have decided to recruit them to your multi-level marketing scheme. Or 1,000 other choices. It’s improv, you get to decide.

But that advice of could vs should also applies to most other forms of feedback. Yes I could make the montage shorter or slower, or I could not. While I 100% appreciate that the feedback was given, I can also choose what I want to do with it.

And that’s true of all feedback. Even feedback that says, “Do x or you’re fired,” you could choose to get fired (you just may not want to).

The one caveat I will say to could is to also take into account how many people give you that same feedback. If one person gives you a piece of feedback, that may just be their opinion. If 10 people give you the same piece of feedback, then it might really be worth considering.

So, fine, I won’t wear a onesie on stage.

What about you?

How good are you at asking for feedback? How well do you tend to take it? Any feedback you have for me on these newsletters?

Tell me what you’re thinking!

=Drew

PS. We won’t be releasing the recording of the run-through yesterday, but you can join us for two of our upcoming events in February: Writing Workshop on February 7th or our next virtual happy hour on February 29th, where we’ll be talking about taking a “leap of faith.”